The Air We Breathe: DNA, Privacy, and the Future of Forensics

Imagine taking a stroll in your local park, leaving invisible traces of yourself behind with every breath you take, every cup of coffee you sip, and every surface you touch. Now, picture a world where these minute genetic breadcrumbs can be collected, sequenced, and used to learn intimate details about you. This is not a dystopian future. This is now.

In an article by Isabel Seliger, “Your DNA Can Now Be Pulled From Thin Air. Privacy Experts Are Worried”, she introduces the concept of environmental DNA or eDNA. This technology, originally developed by wildlife geneticist David Duffy at the University of Florida, is capable of recovering trace amounts of genetic material from the environment.

Previously, the focus of eDNA was primarily on wildlife conservation, detecting invasive species, tracking vulnerable wildlife populations, and even rediscovering species thought to be extinct. But as Seliger’s article reveals, this technology is not limited to animal DNA. It’s capable of extracting human DNA from the air we breathe and the water we touch. It can gather medical and ancestry information from these trace amounts of DNA, which raises significant privacy concerns. Additionally, the implications of eDNA technology for law enforcement are profound and potentially transformative, but they also raise significant legal and ethical questions.

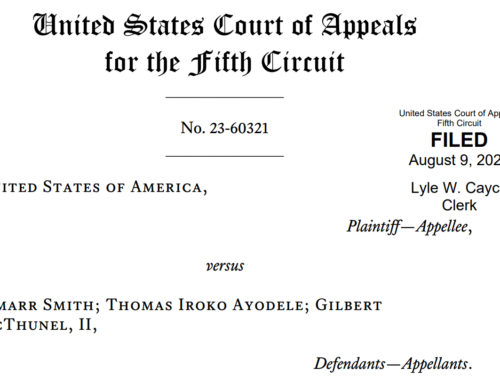

Law enforcement has a longstanding relationship with DNA. Since the introduction of forensic DNA testing, DNA evidence has played a pivotal role in solving countless crimes. It has also been instrumental in exonerating individuals wrongly accused or convicted. However, the potential to gather DNA from environmental sources presents a whole new landscape for law enforcement.

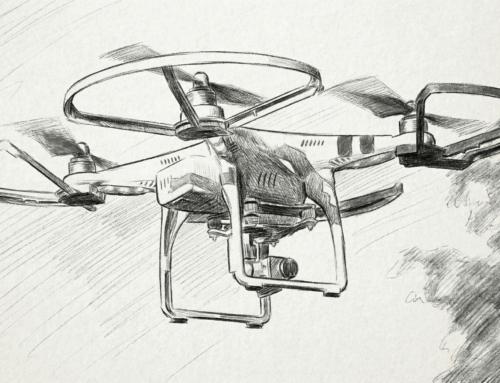

Currently, in the United States, law enforcement’s use of DNA generally revolves around the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS). This system, managed by the FBI, utilizes specific markers spread across the human genome to identify individuals. However, the fragments of DNA recoverable from environmental sources are usually not sufficient for this type of analysis. Nonetheless, forensic researchers suggest that individual identification from eDNA could already be possible in enclosed spaces where fewer people have been, such as inside an office.

This raises the intriguing possibility that law enforcement officials could use eDNA collected at crime scenes to generate leads or even identify suspects. However, such applications would undoubtedly raise significant legal and ethical concerns. One of the most significant of these is the question of the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition of “unreasonable search and seizure” without probable cause. If DNA collected from public places is considered ‘abandoned’, law enforcement wouldn’t need a warrant to collect it. This has potentially alarming implications for privacy, as it’s almost impossible for individuals to avoid leaving DNA in public places.

Furthermore, the quality and quantity of eDNA vary considerably, making it a less reliable source of DNA than direct samples such as blood or saliva. The nanopore sequencing technology used to analyze eDNA has a much higher error rate than older DNA analysis technologies. This could lead to false positives or misinterpretations, potentially implicating innocent individuals.

The use of new DNA collection techniques, like eDNA, is understandably enticing for law enforcement, as it may provide new avenues to solve crimes and bring justice. However, the potential for misuse or overreach is substantial. As we’ve seen with other forensic techniques, such as blood spatter analysis and bite mark evidence, the adoption of new methods without robust validation and regulation can lead to wrongful convictions.

In this “wild west” of DNA technology, as described by Erin Murphy, a law professor at the New York University School of Law, it’s essential to establish clear guidelines and regulations for the use of eDNA in criminal investigations. This should include establishing protocols for collection and analysis, safeguards against misuse, and mechanisms for challenging the use and admissibility of eDNA evidence in court.

Moreover, there’s a need for more extensive research into the fundamentals of eDNA, like how it travels through air or water and how it degrades over time. As the science behind eDNA matures and becomes more understood, it’s critical that legal understanding and regulation keep pace.

While eDNA may provide law enforcement with a powerful new tool, it’s vital to balance the potential benefits with the protection of civil liberties. As we venture into this new frontier, we must ensure that the pursuit of justice does not come at the expense of individual privacy and civil rights.